The following article by Len Stillwell

first appeared nearly ten years ago in issue number 29 of our

Form 700 Regional Newsletter, and tells the story of a young

man's ambition to fly, his operational training, and of service

life on an RAF Squadron overseas during the war. It is now

reproduced below, in full, and we do hope that you enjoy the

following piece as much as we enjoyed rereading it.

For many people the training route to

becoming a pilot was much the same, and so this story will

hopefully bring back fond memories, and for those of us too

young to have served during the war, it provides a wonderful

insight for which we owe our thanks to Len.

Len flew Spitfire Mks VIII

and IX, with their distinctive white flash on the fin, over

Italy and Austria, with the famed Battle of Britain Squadron,

no. 92. What Len does not mention here is that whilst on a sweep

over Italy his Spitfire was hit by an anti-aircraft shell

severely wounding him in both legs; an injury which always

remained with him. In spite of this, Len was back flying

again after a short R&R break.

Sadly, during a spell in hospital, Len

Stillwell died in early December 2008.

We feel that the following article is a

fitting memorial to our dear friend; an obituary will appear in

the next Form 700 Newsletter.

Len served on the Eastern Region Committee

for many years right up until the last months of his life and

was always pleased to help younger Committee Members with

valuable words of advice and wisdom.

In June of 2008, Len’s wife Dorothy (or Dot

to all who knew her) died after bravely battling illness for

some years, during which time Len was her pillar of strength.

Since the early days of Eastern Region, Len and Dot were always

a familiar sight at Society events and air shows and in common

with our other ‘Regulars’ have helped to raise many thousands of

pounds for the Spitfire Society.

Len and Dot were two of the most loved

members of our team and always represented that which is best

about the Spitfire Society.

P.W. December 2008

--------------

Becoming a fighter pilot is

not and never has been easy - even with the urgency and impetus

of war. We all are, at times, beneficiaries of luck or good

fortune in whatever we undertake and I certainly had my fair

share of both - I hope this story will show that, but I must

explain that it will say very little about my combat experience.

More, perhaps about the journey I undertook (in common with so

many) and the things that happened along the way.

L.S. June 1999

DREAMS OF FLYING

As a child in the early

'thirties I dreamed of flying and piloting a plane and my father

took me on two occasions to the Hendon Air Display. I thrilled

to see wonderful biplanes such as the Bulldog and Fury perform

aerobatics in neat formations and joined together by coloured

tapes.

My first experience of flight

was at Blackheath in South London. Alan Cobham's Flying Circus

was on the Heath and my sister and I took joyrides in a large

twin engined biplane. I was a boy scout and longed to join an

air scout troop, but they were few in number then.

In 1938 the Air League formed

the Air Defence Cadet Corps, which was more to my taste. Our

uniform was based upon that of the RAF and we attended parades

and lectures given by RAF personnel and visited local RAF

Stations. It was at RAF Biggin Hill that I remember first seeing

the new Hurricane fighter.

War came in 1939 and I was at

school in London. I tried to join the Auxiliary Fire Service but

was rejected as being too young. I did, however, during the

Blitz, drive a mobile canteen around Air Raid Shelters when no

other driver was available.

JOINING THE AIR TRAINING CORPS

Then the Air Training Corps

was formed from the nucleus of the ADCC and I immediately joined

the local squadron.

Training and instruction in

many disciplines was more professional and examinations for

Proficiency Awards were held. Many weekends were spent at RAF

Balloon Command HQ at Kidbrooke, where cadets helped out with

many non technical tasks. I spent much of my time in the Signals

section where messages and orders were received and passed on to

Balloon sites.

The visits I enjoyed most were

the annual camps in 1941 and 42 at RAF Biggin Hill. It was here

that I had a flight in a Magister and the pilot allowed me my

first hands on experience of flying. I also sat in a Spitfire

while a fitter leaned into the cockpit and started the engine -

a great thrill.

At the age of 17 I volunteered

for air crew training. At that time you could not apply for

pilot training only but had to apply for the group which

included pilot, navigator and bomb aimer (known as PNB). Your

suitability for your eventual trade was supposed to be

determined by aptitude during your training period.

We had Aldis lamp practice in a local park and

range shooting with rifle, revolver and sten gun. Clay pigeon

shooting also featured heavily in the syllabus. Vigorous

physical training was interspersed with long cross country runs

up and down the local hills and we played inter flight rugby. At

the end of the course we went on leave a bit wiser and a lot

fitter.

HOSPITAL ATTACK

Whilst on leave, I became

unwell and on my return I reported sick. I was sent to the sick

bay which was located in a local hotel, which had been

requisitioned by the RAF as a hospital and convalescent centre.

As I sat in bed, one Sunday afternoon, looking out to sea, I

noticed three low flying aircraft heading for the shore. I felt

sure they were friendly, when suddenly every anti aircraft gun

in the area opened up. They turned out to be Me109f's.

In spite of big red crosses

prominently painted on the roof of the hotel, they bombed and

strafed the building, killing and wounding many of the

occupants. We later learned that they had earlier attacked the

local district of St Marychurch and scored direct hits on a

church hall full of children. Many were killed.

GRADING SCHOOL

On being passed fit for duty I

returned to the ITW and having passed the course, was posted to

Grading School at Theale near Reading. This was where my

aptitude as a pilot would be assessed. I carried out 12 hours

dual instruction on Tiger Moths where all the basic manoeuvres

of climbing, turning, spinning, stalling and descending were

taught and examined. Twelve hours in a real aeroplane - I just

had to pass!

We also had to take turns on

night guard duty as well as setting out the flare path when the

instructors were night flying. A dash of rum in the hot strong

cocoa helped to wash down the doorstep bully beef sandwiches.

The completion of the course

saw us sent home on embarkation leave. Saying goodbye to family

and friends without the slightest knowledge of where you are

going or how long you are likely to be away is not easy, so it

was with some trepidation that I left home for Heaton Park,

Manchester, just hoping I had made the pilot grade. Four of us

were billeted together in a house at Salford. Our days were

spent rather aimlessly at Heaton Park, our weekends mainly in a

YMCA canteen in Piccadilly, Manchester.

RHODESIA BOUND

After three weeks we were

paraded and given our grades. I was selected for pilot training

and posted in a draft bound for Southern Rhodesia. We were sworn

to secrecy and then issued with tropical kit and subjected to

numerous inoculations. Very early one morning we piled into

trucks and were taken to the railway station where we caught a

packed troop train for Glasgow. After many hours we arrived at

Gourock on the Clyde and were transported by tender to our new

home - a converted cargo liner, the 'Llangibby Castle', which

was dwarfed by the presence of the 'Queen Mary'.

Crammed into the lower decks

with several hundred men, we were shown how to stow our kit and

provided with hammocks and life jackets. Once on, I don't think

we took the latter off, even when sleeping, fully clothed.

Conditions were grim and

became even worse when we ran into bad weather. Battened down

below we were violently sea sick and the constant rolling and

pitching of the ship sent the buckets provided sliding all over

the wet floor. No one could eat and we fervently prayed that

there were no U Boats in our area.

As the gale subsided we were

allowed on deck for brief periods and we could see the other

ships in the convoy and our escorting aircraft carrier and

accompanying naval vessels. Despite the heavy seas, the carrier

flew off several Swordfish and we watched one miss the arrester

wire as it landed and it bounced off the flight deck into the

sea. No rescue was attempted.

We had little to do, other

than write letters which were heavily censored and wait

hopefully for our ship to reach a port. Our hopes were cruelly

dashed. Our ship was suddenly diverted from its course down the

west coast of Africa into the Mediterranean -without even

stopping at Gibraltar. All available transport was needed for

the invasion of Sicily and we were joined by numerous other

transports and warships.

Along with the others our ship

was heavily armed and frequently we were herded below when at

Action Stations and heard and felt our guns firing. No damage

occurred and the only aircraft we saw were American P38

Lightnings. After several days of this we arrived at Port Taufiq

at the southern end of the Suez canal, where we disembarked. The

first part of our voyage was thankfully over.

CAMELS AND SCORPIONS

We were sent to a transit camp

where we slept under canvas and were plagued by flies and the

intense heat. Water was issued once a day and the food was of

doubtful quality - dry bread, margarine and cooked meat, which

the cooks assured us was stewed camel.

Toilets were just pits with

multi holed seating, but our one luxury was a communal shower.

We were marched for about an hour to the ablution area and then

stood around awaiting our turn. Water was delivered to this

point in pipes laid under the sand, so was reasonably hot.

Eventually we were marched into a canvas screened area, stripped

off and walked on duckboards under pipes gushing water. What

bliss to be clean again.

The unbearably hot day was in

sharp contrast with the bitterly cold night and our single

blanket did little to keep us warm. Very soon many of us were

suffering from dysentery because of the conditions and I

suffered a scorpion bite to the throat and was dispatched back

to base hospital. By the time I had recovered, my draft had

moved on, so I had to wait for another ship to take me on to

Durban.

Joining the 'Empire Trooper' I

found it contained mainly South African troops, but there were a

few RAF trainees aboard and it was here that I met Dennis

Richardson, who was to become a very close friend during our

service together and later into civilian life.

As we sailed down the east

coast of Africa the stifling heat forced us to sleep on deck and

it was a great relief to enter Durban harbour. We were greeted

by the sound of a wonderful female soprano voice and were

astonished to see a lady dressed in white and wearing a broad

brimmed red hat singing unaccompanied to the convoy as it sailed

in. 'Land of Hope and Glory', 'Roll out the Barrel' and many

other favourites were delivered across the still water.

I later found out that her

name was Perla Siedle Gibson and from 1940 until 1945 she

provided this unique welcome to many thousands of service

personnel who arrived in Durban this way.

ARRIVAL IN RHODESIA

We spent a short time in

Claremont Transit camp and then joined a very long train for the

journey through the magnificent scenery of the Drakensberg

Mountains and past Lady smith. After two nights on the train we

arrived at Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia and were sent to Hillside

Camp - a former cattle market - where we were billeted in the

former cattle stalls. I spent Christmas 1943 at Hillside, having

Christmas dinner served to us by the officers.

We were given a further ground

course at Hillside ITW and then posted to No.25 Elementary

Flying Training School (EFTS) at Belvedere, near Salisbury. We

trained on Cornell PT26's and our training was often interrupted

by the flooding of the airfield, during the rainy season. I

remember being caught by a massive thunderstorm, whilst flying

dual and we were forced to land at a tiny satellite field and

take shelter in a thatched hut. A field telephone link told us

when it was safe to return.

At the completion of our EFTS

course Dennis and I were selected for single engine aircraft.

Those selected for twin engine training left us to go their separate ways. We

moved across Salisbury to No. 20 Service Flying Training School

(SFTS) at RAF Cranborne, where we flew Harvards.

Cranborne was an airfield with

a hump in the runway - much like Biggin Hill. During take off

you could not see the far side of the field until you had topped

the rise, so both take offs and landings were fairly

interesting.

Living accommodation at SFTS

was very much better and we had the use of the sergeant's mess.

Our training now included sessions in the Link Trainer learning

instrument flying and ground controlled approach as well as

numerous cross country flights by day and by night.

One moment of light relief was the making of a

film by the Ministry of Information about the contribution that

Rhodesia made to the Empire Air Training Scheme. We were posed

in groups around aircraft listening to instructors and filmed

climbing in and out of the cockpit, as well as taxiing along the

runway. The climax of this film was a mass formation of Harvards

(all flown by instructors). Every serviceable aircraft took part

and most impressive it was to watch.

Flying finished at noon on

Saturday and we were free to spend the remainder of the weekend

in Salisbury. We stayed at the Troops Hostel and swam in the

open air pool. We also got to know some local families who

offered us friendship and hospitality, which was much appreciated. Much of our

time was spent at the cinema, where we avidly watched newsreels

of the progress of the war.

GETTING MY WINGS

My time at SFTS was drawing to

a close and examinations and final air tests by the CFI led to

qualification as a service pilot. A few of our mob failed and we

didn't see them again as they were sent off to remuster. The day

of the Wings Parade came and we made commendable efforts to look

smart and tidy as we received our Wings.

Following the parade we

returned to our billets to find the next draft of sprog pilots

moving in. Leave followed, and my friend Dennis Richardson and I

caught the train to Livingstone and went to see the Victoria

Falls.

EGYPT POSTING

Returning from leave we

received our postings. Ten of us (Dennis included) were posted

to an OTU in Egypt. We left Cranborne in a Lockheed Lodestar (in

BOAC markings) for Kano in Nigeria and the following day flew on

to Khartoum in the Sudan. The final leg of our journey took us

to Cairo where we were billeted in the Heliopolis Palace Hotel.

We spent some time in Cairo, enjoying ourselves in the French

quarter and guarding our belongings from the skill of the

fellaheen who could divest an unwary victim of anything without

being detected.

FIRST SPITFIRE FLIGHT

Our period of luxurious living

ended when we were moved to a tented transit camp and subjected

to numerous fierce sand storms. From here we eventually

travelled to 71 OTU at Ismailia in the Canal Zone. Here we flew

Hurricanes and it was on 15th January 1945 that I achieved my

ambition when I flew my first Spitfire - Mark V EP708. I cannot

remember my feelings at the time, but it seemed a significant

milestone in my career.

At the end of our course we

went on a further period of leave and managed a trip from Cairo

to Jerusalem (a train journey I wouldn't want to repeat). The

Holy Land was slightly disappointing and it even snowed when we

were in Bethlehem.

We left Egypt by Dakota for

Rome, via Malta, and on arrival I was posted to a Refresher

Flying Unit (RFU) where I converted to Mark IX Spitfires. Our

runway was a section of a straight tree lined road, which was

heavily cambered. Take offs and landings in the much heavier and

more powerful Spitfire were quite hair raising at times.

We flew and practiced battle

formations and at the end of the course I was officially a

fighter pilot, although I didn't feel like it at the time and

realised that I had a lot to learn.

92 SQUADRON

From the RFU I was posted to

92 Squadron, part of 244 Wing. This was a fighter/bomber

squadron and our principal task was close ground support of our

forward troops. All the squadrons on the Wing had to be totally

mobile in order to keep up with the rapidly changing situation.

This meant that everything that was necessary to support

operations had to be capable of being packed into a lorry or on

a trailer. Even unserviceable aircraft were moved on 'Queen

Mary' low loaders.

Ground conditions varied

enormously and we relied on the Royal Engineers Airfield

Construction Units to move forward - often under fire - and lay

Pierced Steel Planking (PSP) for runways. Landings had to be

very precise because if you ran off the end or sides the

aircraft might easily tip over or end up in a quagmire.

Personnel were billeted under canvas or in whatever buildings

were close at hand. The quality of the food we ate varied

enormously, but a resourceful Mess sergeant could very often

conjure up fresh meat and vegetables instead of the dreary and

unappetising tinned M & V, bully or baked beans.

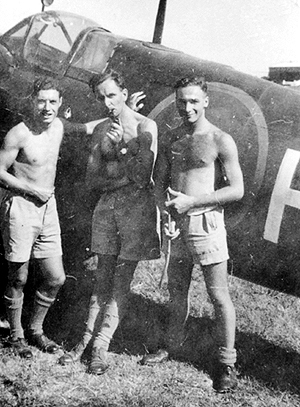

The intense heat found us

wearing nothing but shorts, except when we flew. Then long

sleeve shirts and trousers were the order of the day. The longer

our aircraft stood in the sun, the hotter they became and it was

necessary to wear gloves, even to touch them. Sitting in the

cockpit at readiness or waiting engine start up wearing helmet,

Mae West, parachute and tightly strapped in with the Sutton

harness was absolute agony. How we longed for the fan to start

turning. Once the engine was running, we got off as quickly as

possible to avoid overheating in such temperatures.

Things were so different in

the winter and the rainy season. The rains seemed to last for

weeks on end and what had been fine, choking dust became thick

squelching mud.

Getting around was impossible

and we rarely took off our flying boots - except when we flew

that is, as they were never worn for that purpose. Our clothes

were permanently damp and it was also exceptionally cold. If we

managed to find a relatively undamaged building to live in, we

relied on our ground crew to rig up a rather dangerous drip feed

heater, which used petrol or kerosene. The fumes were dreadful

but the cold was even worse.

AFTER THE WAR

The end of the European war

found me in a field hospital, recovering from wounds inflicted

by flak. When I returned to the Squadron there was speculation

that we might be shipped off to the Far East to fight the

Japanese and we were glad when that conflict also ended.

From Bellaria we moved further

north to Treviso and the Wing was stood down for a month. We

relaxed in rest camps set up in

Venice and Cortina and skiing

became quite popular. Our mobility was curtailed, however, when

the German and Italian Army vehicles we had 'liberated' were all

confiscated.

One notable memory that I have

of that time was the Open Day that we organised for the local

population. We set up marquees and the cooks excelled themselves

by producing large quantities of sandwiches, cakes and jellies.

Within an hour of hundreds of local people and children arriving

the whole lot had gone - hardly surprising in the circumstances.

The good times did not last

long as we were moved to Zeltwig in Austria. There was tension

between the Allies and Marshal Tito, who had taken power in

Yugoslavia, over disputed Italian territory. The Wing was put on

stand by in case of trouble. Our base was a former Luftwaffe

airfield and there was a huge pile of wrecked German aircraft on

the dump. We were billeted in wooden huts and conditions were

tolerable in summer as we were about 5,000 feet up a mountain

valley.

The winter was bitterly cold

and flying became difficult and dangerous. Constant snow

clearing of the runway was necessary and life seemed to be one

long working party. Thick snow in the mountains cut us off from

our supply base and we were reduced to very basic rations,

although we did manage to supplement these with some game birds

that we shot and scrounged turnips and potatoes.

Because of the Tito emergency

our tour expired and demobilisation leave was suspended and this

caused a great deal of anger and resentment, especially with

those who had many years service. An officer of Air Rank was

flown in to try and reduce the tension and we were all paraded

to be told that the situation would soon be resolved, but in the

meantime the Riot Act would be formally read to us. This having

been done the top brass smartly disappeared. Fortunately the

situation was stabilised shortly afterwards.

BACK TO HOME

Some six weeks later I left

the Squadron for the UK. We travelled by train from Klagenfurt

to Calais in an unheated baggage truck, riding on top of wooden

boxes. We stopped every few hours when food was dispensed and

after two days arrived at Calais. The crossing to Dover was very

rough but we came on deck to see the White Cliffs through the

mist. After a short journey to Shorncliffe Camp we caught trains

for home.

It was good to be home again

after three years away from England. To swop experiences with

friends and family and to try and settle back into some sort of

normality. I was posted to RAF Oxbridge where I did nothing

except report every morning and then return home.

When my demob number came up I

travelled to Preston and was demobilised. My wartime service as

an RAF Fighter Pilot was over. When I look back I realise that

although I had to endure difficult and sometimes dangerous

conditions, the situation was just as bad, if not worse for many

of those who had to stay and continue to work at home.

We were all in the war

together and this is just one tiny, insignificant story of life

in those times.

You might like to know that signed drawings /

photos of Len and his aircraft are available from the Spitfire

Society. You can find further details here:

The Spitfire Society Interview with Alex Henshaw can be found here:

& previous interviews with Bert Harman:

& Audrey Morgan: